From the temple, the city sounds remarkably peaceful. Where there would usually be the shrill cries of merchants, the scuffling feet of children, and the chatter of women gathering water, there is silence. The streets are empty of carts and horses. Even the dogs are silent, scavenging scraps warily and in increasing desperation, knowing that something is afoot.

The dogs are lucky, Hannibal considers: they are likely to have some decent meals soon, at least those nimble enough to have escaped being eaten themselves. When the city falls, the carrion-birds will arrive just in time to share the meal with their canine fellows. The men that fall in the streets will be the dogs’ portion, to be eaten where they lie or dragged away to a private spot to munch on at leisure. Crucifixtions, while inaccessible to dogs, are the favourites of the birds; they provide a handy place to perch while eating, and the meat is fresh for days as it hangs between life and death. After a siege of seven months, with the city barricaded by citizens pushed on by defiant leaders, there will certainly be enough crucifixions to keep all the winged scavengers happy.

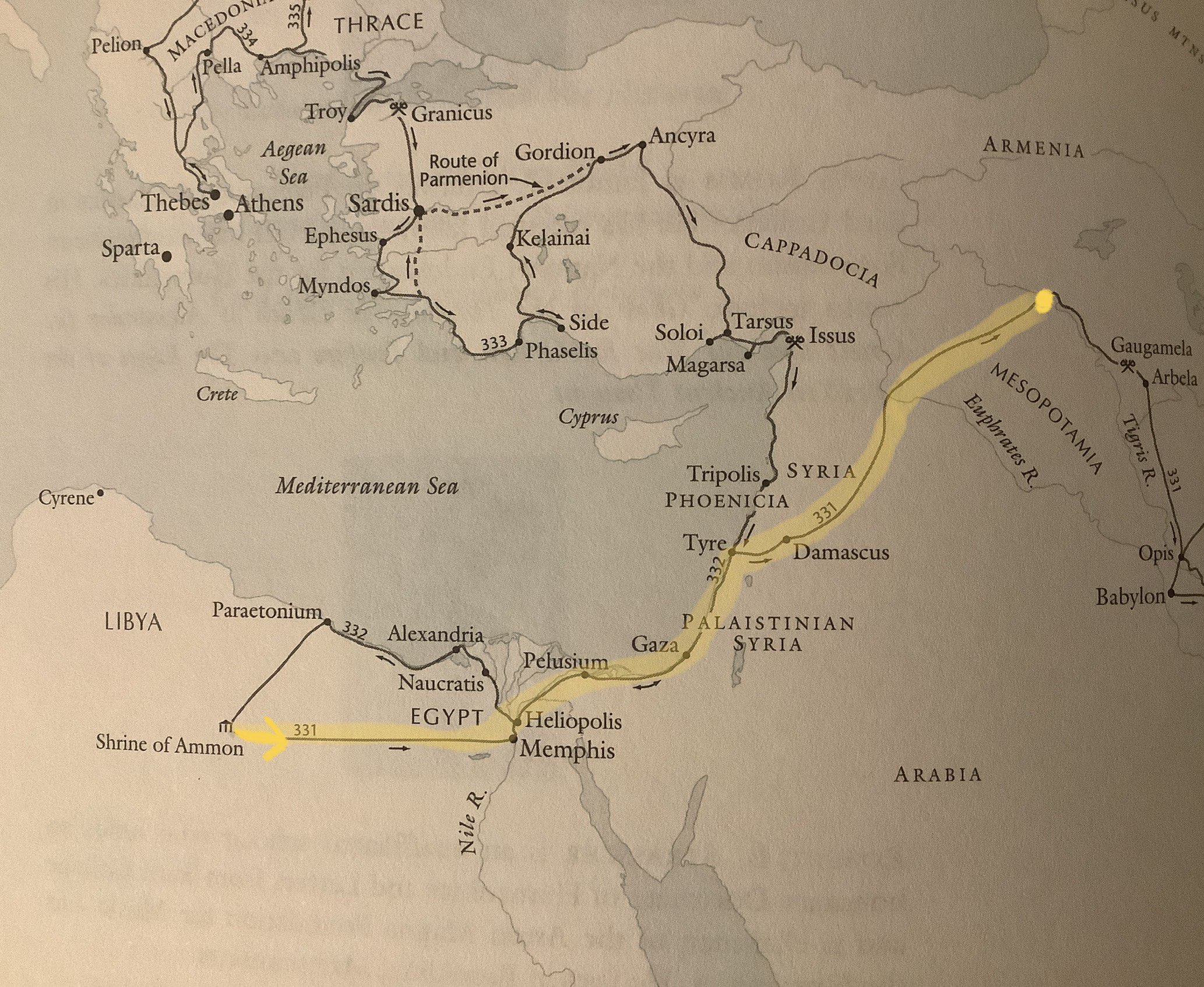

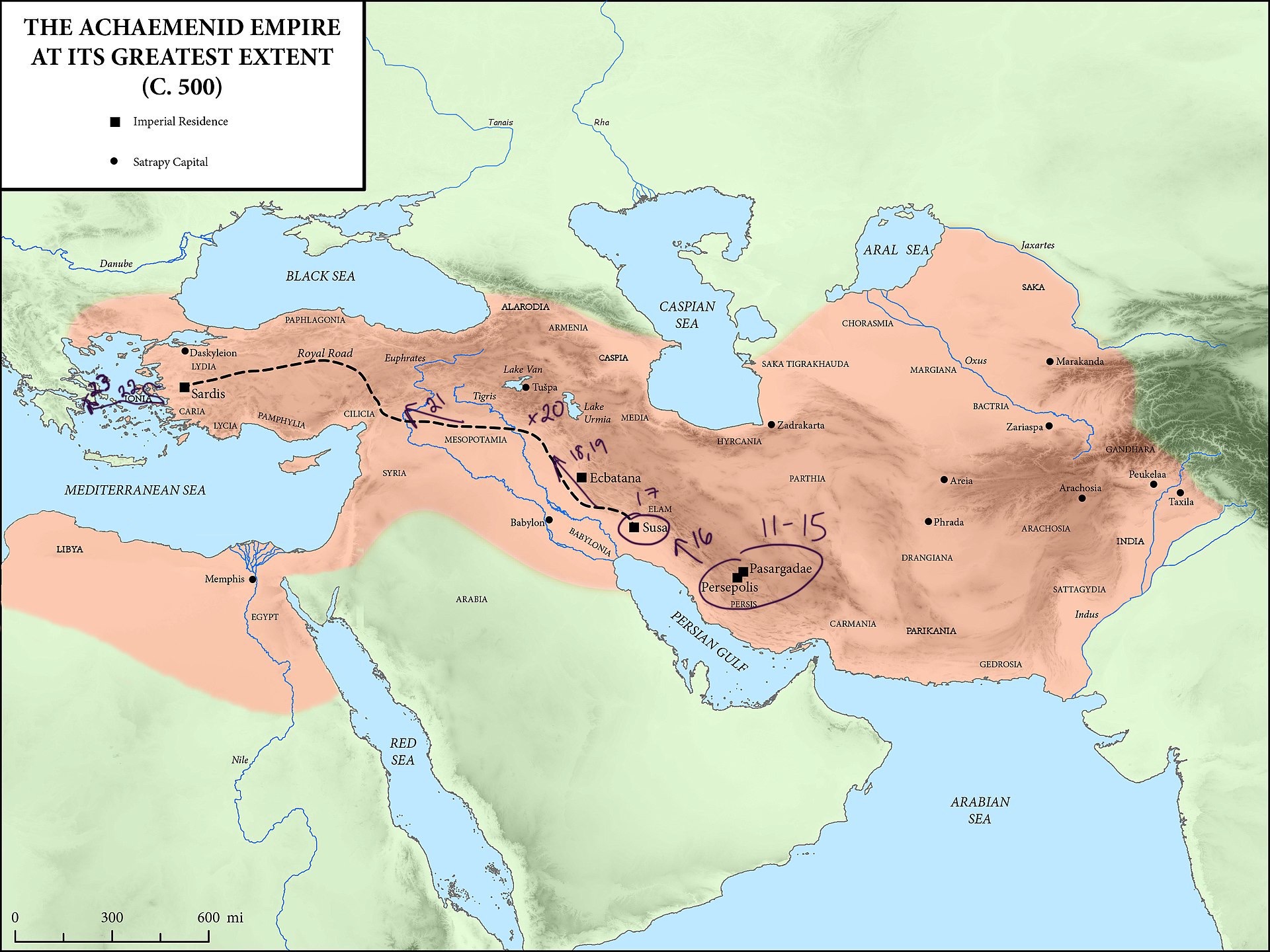

All of the usual noise of the city is concentrated on its perimeter. Tyre’s walls are 150 feet tall and proportionately thick, surrounded by the sea on all sides. A god protected by such a wall-- as Melqart, son of Baal, Protector of the Universe, is-- ought to feel himself untouchable. But Hannibal has been on the walls: he has seen the narrow sand-spit that connects the island to the mainland being built up with stones and wood wide enough for siege-engines, and then the engines themselves placed on towers screened off from the flaming arrows being hurled from the Tyrian walls. He has also seen the ships: the initially weak Macedonian navy has expanded, and it has expanded with Hannibal’s own kinsmen. The Phoenicians serving in the Persian navy had deserted to the league of Hellenes in the spring; now, in the heat of summer, a true naval force has gathered around the inevitable victors in the Tyrian siege, hoping to take part in the spoils.

Not that having Phoenicians in the enemy fleet will soften the fate of the city Phoenicians hold dear. The Macedonians are too eager to finally see the spoils of war to be held back, once the incessant pounding of the siege-engine on the wall finally results in a breach. Tyre will fall, and its men will die. The women, who had been evacuated to Carthage back when it had seemed like just a precaution, will be widows. That fate was sealed on the day the Tyrians had refused Alexander admittance to the city to sacrifice to Melqart, the god he calls Heracles.

Standing at the front entrance of the temple of Melqart, his hands clasped behind his back, Hannibal cannot bring himself to regret it. That he will die with his blood-feud unavenged is unfortunate, but that is what sons are for-- or at least, so he is telling himself. He could not have made better choices with the available information. Perhaps nothing at all would have prevented this.

Behind him, the priests huddle around the god. There are no worthy sacrifices left to be made to him; they have been cut off from trade for months now. Ahirom, the chief among the priests, is chanting something to the god, as if he might make excuses for the empty altar. Ahirom, though young, has taken de facto leadership of the Carthaginian envoys trapped in Tyre for the past seven months. He’s honest and hardworking, if somewhat cowardly. But then, Hannibal cannot expect priests and the sons of priests for generations to comport themselves like the hoplites whose company he remembers fondly from his own early manhood.

Ahirom’s fear is getting the better of him now. For days he has been praying to the god day and night for the benefit of the city; now, his entreaties take on a desperate edge that speaks of their being mainly for himself. He does not want to die.

Hannibal doesn’t want to die either. He enjoys life-- enjoys it perhaps more than the others around him see or understand. And yet, the value of life can only be made clear by the presence of death. He wants even less to lose his dignity. If Melqart wills them to die, then die they will-- and it is beginning to seem that that is precisely what he wills.

Hannibal, and the Tyrians whose vote on the matter he had not been allowed to participate in but whose outcome he had wholeheartedly supported, had had good reasons to choose as they did. They had thought that they were protecting sacred traditions, by refusing Alexander entrance. And after all, they had given up much to the would-be conqueror: they had sent to him that they would obey any command of his, but would not receive any Persian or Macedonian inside the walls of Tyre. It should have been enough. But it was not, and it is beginning to seem that the god was on the young Macedonian’s side all all along. Melqart should have received sacrifice from him months ago, and how he is angry.

Ahirom comes to join him in the entranceway, peering out into the empty street. His face, clean-shaven to mark him as a priest, looks younger than he really is. “Maybe we should barricade the temple,” he says.

Hannibal keeps his face entirely still, not betraying his scorn at the suggestion. It’s an idea born of panic, nothing more. There is nothing in the temple to barricade the entrances with; and even if they did, once the Macedonians have entered the city, there will be no keeping them out of any building. Hannibal plans on dying in combat. He is determined that his remains, whether or not they receive a burial, will at least wear their wounds on the front and not the back. Barricading the doors will decrease the dignity of his death without prolonging his life by more than a few moments.

“Walk with me,” he says to Ahirom.

The priest glances nervously around the street, as if marauding Macedonians might burst around the corner at any moment. Which isn’t too far off from the truth, but they will at least have a few minutes warning: the temple is in the heart of the city, and they will hear the roar of the wall being breached.

“We will only go around the perimeter of the temple,” says Hannibal, and Ahirom reluctantly steps out to join him.

Before Hannibal can say a word, Ahirom is rambling. “I can’t believe this. We should be home by now. My sister is getting married. He must be telling us something. If we can just find the right sacrifice, the god will turn the tide of the battle. It must be so, I can think of no other explanation--”

His stream of words stops suddenly short as Hannibal steps up behind him, takes hold of his chin in one hand and his forehead in another, and snaps his neck.

Ahirom, son of Ahinadab the high priest of Melqart in Carthage, spiritual head of the Carthaginian expedition to Tyre for the festival of Melqart and ceremonial bearer of a tenth of all Carthaginian revenues to the god of its mother-city, crumples to the dusty ground in a heap of limbs.

Hannibal stands over him. His heart is still very steady, as it always is, but he’s breathing hard. He feels elated.

He hadn’t been at all sure that that was even going to work. He’d seen the manouvre once, years ago, during the squabbling over control of Syracuse. Carthage had sent her army in to take advantage of the chaos, nothing more. Hannibal and his fellow hoplites of the Carthaginian Sacred band-- that pale imitator of its Theban namesake, a copy in title but not in concept-- were fighting for Hicetas, tyrant of Leontini, when Hannibal had badly wounded a man who then got away from him before the killing blow. He’d seen from afar, while otherwise engaged, the man clutch the innards spilling from his belly and stumble towards his friend, who disengaged himself from the fighting for long enough to attend him somewhat out of the fray, by a small stand of trees. The friend had removed the wounded man’s helmet, kissed him tenderly all while turning him around to face forward, then taken his forehead in one hand and his chin in the other and twisted sharply. Hannibal had nearly been run through himself, distracted as he was by the movement; its grace, its efficiency in either dispatching an enemy or kindness in showing mercy to a friend. He’d always wanted to try it. Now he has.

It was impulsive, but he cannot bring himself to regret it. He considers his options for a moment. If he stays out until the Macedonians take the city, he will be killed in the street and the dead body beside him will hardly matter. But the idea is unpleasant, cowardly in its own way. Ahirom ought to be in the temple of his god when the Macedonians come, no matter what they choose to do with the corpses of their defeated enemies. Hannibal makes his decision swiftly, and bends down to scoop up the body in his arms. He’s light; since Carthage, unlike the Greek states, has no mandatory military service for civilians, the sons of priests destined to be priests themselves are rarely as burly as their Greek counterparts.

All eyes turn to him as he re-enters the temple. The native Tyrian priests and acolytes are all here; it has been weeks now since they performed, in the presence of the delegation from Carthage, the annual ceremony of death and rebirth that they thought they had come to witness. The remaining members of the delegation from Carthage hover around the edges. Some are priests, and still more are like Hannibal, well-regarded fighting men attached to the delegation for practical purposes. Not that a small attachment of former soldiers is going to do much good now.

Their faces are shocked as he enters with Ahirom in his arms, but a kind of shock worn down by horror and approaching resignation. Nothing can truly horrify them any more. Ahirom’s body is still warm and lax in Hannibal’s arms, as if he were merely sleeping. His eyes are open, staring. The noise outside has gotten louder. And changed in timbre. The Macedonians have breached the wall, then. The door bangs open, but it’s only the Tyrian king Azemilcus, with a small gaggle of magistrates, come to cower in the temple. Hannibal pays them no mind.

Instead he positions himself in the centre of the room, equidistant from the entrance and the altar. Facing the god. The silence rings, even the new arrivals cowed into confused acceptance of the scene, and he takes the time to enjoy it. This is probably the last time in his life that he will hold the attention of others, and it is sweet.

“A final sacrifice,” he announces.

For a moment, everyone just stares. Then they start nodding and murmuring. “Yes,” Hannibal hears the young priest Himilc whisper. “Hannibal is right. It was the only thing to be done. “It’s just,” he hears Barekbaal answer-- silly old man that he is-- “Melqart prefers children in times of crisis. And Ahirom was more than twenty.” “Well, if you’d guessed that he wanted a child, you should have said so before we packed them all off with the women to Carthage!” comes a hissed reply, the provenance of which Hannibal can’t identify. He simply waits for them to come around to his point of view, which they do.

There’s no official consensus; with Ahirom gone, there is no obvious person to take charge of such a thing. But all eyes in the room turn to him in desperation; begging for the help that only he, with the sacrifice in his arms, can bring.

Hannibal makes his way towards the altar, the never-extinguished fire. There are voices in the street, the yelling of elated soldiers growing closer. Soon all of this will be lost to screams, blood, the stink of sweat and rot. The next few moments, however, still belong to him.

In any other situation, he would retreat to the edifice at the centre of his mind for such a moment: the temple of Athena and Zeus the City-Protectors at Rhodes, a place that he had seen once and immediately decided he must bring as much of it back with him as possible. He had managed two pieces: the first one being the airy atrium of the temple, filled with scrolls, as an entrance to the building that houses his memories. The second was Alanat, who had come back to Carthage with him, and given him two strong Rhodian sons and one daughter. The first among them, Hamilcar, is old enough to take care of his mother and sister; Hannibal has nothing to fear on that count from his own absence.

Since he is already in a temple, however, retreating to a different temple in his own mind would be superfluous. No, he will stay here until his flesh is pierced by bronze and his eyes can see no longer; only in the final moments, as he waits for death to overcome him, will he retreat into his own mind. Outside the doors of the temple, the timbre of the clamour changes. There are men at the door, but they do not burst through. Instead, Hannibal hears the scraping, shuffling and muttering of a guard being posted. Now they are trapped in here. Hannibal advances towards the altar and places the body of Ahirom gently down on it. Desperate eyes follow him, and he wonders what kind of deliverance they expect the god to send.

Bright sunshine bathes him from the gap in the roof where the smoke escapes, and for a moment Hannibal stares up. His last view of the sky, filtered through a round opening like an eye. Like Melqart is watching from above, as well as within.

It would be appropriate to cut Ahirom’s throat, even though he’s already dead, and Hannibal reaches for the small knife he always keeps on him. It was a gift from his father after an expedition to Libya and Egypt-- intended for practical purposes, not self-defense. After the first time he’d tested it on human flesh, he had only ever used it for meals and sacrifices. All of the weapons in the city had gone to the men on the wall, but Hannibal had kept the knife back.

But before he can draw the knife out of its leather sheath, and before Ahirom’s clothing can even begin to catch fire, the door swings open. Hannibal turns. He has no weapons but the knife, but he will fight with that, and then with his hands, until he can’t any more.

The soldiers who enter the temple cluster around the Macedonian king like iron to Magnesian stone, such that it would be immediately obvious which one he is even without the plumed helmet he holds in his hands. Hannibal’s first thought is that if Melqart did want an adult man as a sacrifice today then Alexander son of Phillip, and not Ahirom, is exactly the sort of victim he would choose. He is shorter than many of the men around him, and clean-shaven; he would be easy to mistake for a youth, if it weren’t for the gravity in his eyes and the obvious regard of his bodyguards. He is also virtually drenched in blood.

He stares past Hannibal, grey eyes focusing immediately on the altar. “Were you preparing to sacrifice?” he asks. His Greek is slightly lopsided, the merest tinge of his Macedonian native tongue seeping in. He had the best tutors in it, surely.

“Tell him it’s for him,” Hannibal hears a hiss in Phoenician from behind him. He is, he realizes, the only one among them with passable Greek; that had not been considered an important quality in choosing the delegation to Tyre.

It would be the intelligent thing to do. Step back, tell the conquering barbarian that the sacrifice was killed for him, to welcome him, and all that is left for him to do is burn it. He does not know, surely, that Melqart demands human sacrifices only rarely, and children on such instances. He will readily believe that the wild lands he has entered regularly dedicate men on their altars.

Hannibal would rather die. He had been prepared to die, after all, and is still unsure what form this question means such death will take. If they are enslaved, he will find a way to take his own life before he is sold. It would be easier to get it over with now.

“We were,” he says instead, and nothing further. Although none of the Phoenicians behind him speak fluent Greek, they can certainly understand well enough to know that Hannibal had not just invited Alexander to share in the dedication. The tension is, if anything, even tighter. Why, Hannibal wonders, when they are all dead men anyway? Surely the Macedonians will have no compunctions about slaughtering men even in a temple, for all their civilized Greek trappings and airs. His travelling-companions from Carthage would therefore, surely, be much more comfortable if they relaxed with the inevitability of their own deaths. They are all dead men.

Alexander looks almost amused. He shares a private glance with the man standing beside him, then says, “Well, I’ve waited this long; surely your Heracles will accept two sacrifices on the same day. Finish your sacrifice; you, Tyrian priests, will have your lives. And--?” he turns to Hannibal.

“I am one of the thirty men come from Carthage for the festival of Melqart,” says Hannibal.

Alexander looks thoughtful. “And how did you get here?”

Hannibal briefly considers the insulting answer-- on a boat, or did you think we swam?-- but decides against it. There is nothing to be gained or lost at this point. “The sacred ship upon which we sailed has been carrying the Carthaginian tribute to Tyre for many centuries.”

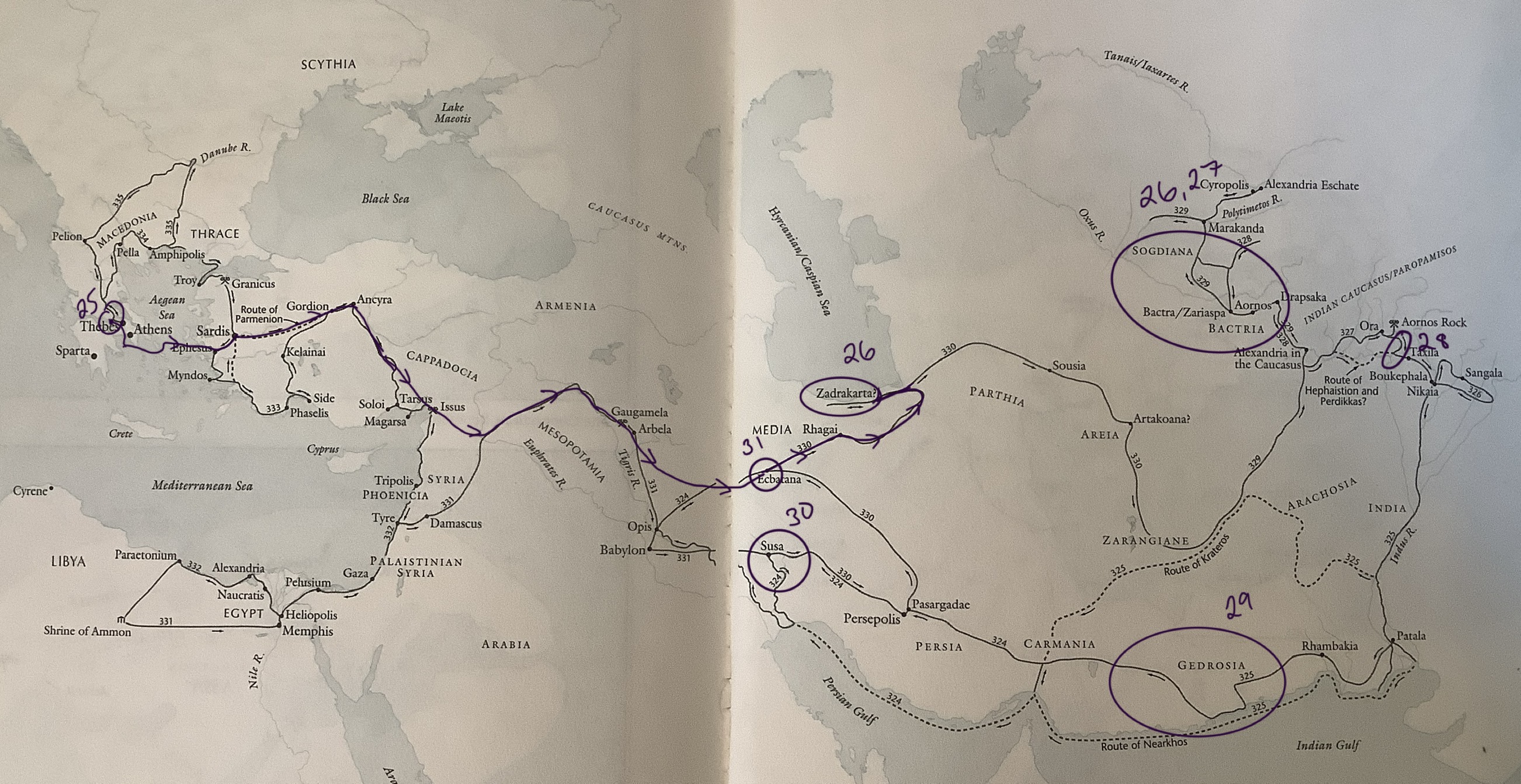

“Good. I will have it to dedicate to the god. And you, seafarers, will have a trireme to get home on; so that you can tell your city that her turn will come once the conquest of Asia is complete.”

And with that, the dead men assembled in the temple of Melqart live once again. They had come to Tyre to honour the death and rebirth of the god in the heat of the sacred fire; instead, they had died and are now reborn themselves. As Hannibal builds a pyre with which to annihilate Ahrom with the Macedonian king watching interestedly, he wonders whether the god may be present not just in front of him in bronze, but also behind him in flesh.

There is no particular moment when he decides to step back and hand the torch to the king; he simply finds himself doing it. “Hannimelqart,” he says to Alexander, a naming; for that is how he will think of him from this day on. Beloved of Melqart.

Alexander flinches for the sparest moment; he has never sacrificed a human before, Hannibal deduces. But in an instant-- and with a barely-perceptible nod of encouragement from the friend who has been standing at his side this entire time-- he takes the torch and set the pyre ablaze. There is reverence in his face as he stares up at the flames. Whether his belief that Melqart is one and the same as his god Heracles is sincere, or whether he merely understands that a strong sense of syncretism will serve him well as as conqueror, Hannibal does not know.

But he knows for certain that when the Carthaginian delegation sets out for home, he will not be among them. He has stood on the banks of the river today, and found that the idea of leaving this world with his sister unavenged is more disturbing that he had thought it would be. If there is anywhere in the world that one should begin, to commit one’s self to honourable blood-feud, it is here: among the followers of Hannimelqart, scion of Heracles, soon to be Great King of Persia, Alexander.

So ends the siege of Tyre for Hannibal son of Lectis, in the month of Hekatombaion, during Niketos’ archonship at Athens.

The vision always starts the same: blood.

It’s a sea of blood, stretching out towards the horizon. The water of this sea moves differently from the calm lapping of the oasis, and differently too from the dancing of sand over sand beyond the village walls. It roars and jumps. Wel has never seen the sea with his own eyes, but he knows that must be what it is.

The sea rushes towards him, and he is terrified. But there is nowhere to go; in the vision he is not inside the temple but pressed up against the sheer face of rock upon which it sits. Unlike in reality, there is no set of stairs up the rock. All he can do is watch the blood bear down on him.

When it hits, Wel forces himself to continue breathing. His body, cowering against the figure of King Amasis offering vases of wine to the eight deities, still needs air. There still is air, in the sanctuary. In the vision the blood rushes into him, up his nostrils and into his ears and eyes, under his arms and between his legs. He floats. He has been here before, so he must hold on; every time, the vision goes a little bit farther. Next, he knows, comes the knife. It is both in front of him and pressing into him, nowhere and everywhere; it cuts his skin into strips of agony. He just needs to reach out and grasp it.

He doesn’t; he never does. This time, though, the ghostly presence of the knife coalesces into a single point. It is at his belly, just below his navel. He stares downwards, through the thick red cloud of blood engulfing him, and watches helplessly as it presses in. It hurts, it hurts, but it also--

-- Wel gasps, and lets go of the vision. It feels, every time, like he has been holding onto something brittle at a very great height, and letting go is both failure and relief. His body aches like he has just fallen a long way. His head might as well be split open on the stone, judging from the pain. But his belly is warm, like there really is blood spilling from a wound there. He clutches at it and finds fabric unstained except for his own sweat; and as he curls in on himself on the stone floor, clutching his stomach with relief, he also realizes that his cock is hard. That’s new. It is neither welcome nor unwelcome, just another aftereffect to be waited out. He opens his eyes and stares across the room; there is a pitcher of watered wine in an alcove, but he is too weak to get up and pour himself some. He closes his eyes and waits instead, his mouth parched and tasting of dry blood.

It recedes physically, the sweat drying from his skin and clothes as the memory of the vision tries to run out of his mind like water. This is the crucial part, that he not forget; or rather, not lose the urgency of the vision, the feeling it gave him. He will remember the details, but they will gradually start to seem irrelevant, not worth treating as true prophecy. Joh has assured him since childhood that this is normal. It’s why prophecy cannot be done alone: it must be imparted before the conviction of the moment wears off. It’s why sacrifice, done under the influence of the ecstasy of the gods, is in some ways easier; the victim is still dead when he comes back to himself, even if he can’t remember doing it with any body that belongs to him.

Joh. He has to visit him. Wel had entered the temple towards the end of the first watch; it is now entirely dark outside, the moon only a sliver hanging behind the temple. He manages to scrape himself off the floor, and pours a libation of wine for Ammon-Re before spilling most of his own cup down his chest. He curses, pours the god more wine in apology, and somehow stumbles down the stone steps of the temple without falling flat on his face.

Joh’s house isn’t far from the temple, but it’s out of the way of the main road that leads from the spring to the temple staircase. All of the most coveted dwellings are; nobody wants to have supplicants sniffing around where they live, and in the peak season the garden planted around the spring can be almost as busy as the marketplace in Memphis. Wel is generally occupied in the temple during those periods, and has only seen the hustle and bustle from above. The first and only time he had been taken into Memphis, to bring the oasis’ famed salt as a gift to the satrap, he had nearly fainted from the sheer volume of humanity pressing in on him. Visions had swarmed him like bees, too numerous to understand, interpret or even count. Joh has tried to convince him to go again, that it would get easier. He’s probably right, but Wel refused. He has never imagined any future but spending the rest of his life at Siwah, so why bother?

It’s a cool night. Most people are sleeping inside their houses, instead of on the flat canopied roof that they use on the hottest nights. Sure enough, Wel can hear Maia waking Joh as Wel approaches the house, before Wel even taps on the door. Her soft meow is quickly followed by a rustle and the soft glow of a lamp spilling out underneath the door. When Joh opens the door, he ushers Wel in without greeting him. He looks tired. More than that, he looks old; his beard is definitively grey, and the loose skin under his eyes overlays a mottled purple on brown. Wel wonders if that’s something that happened gradually, and he simply never noticed the change in the closest thing he has to a father, or if it’s recent.

Wel has been making more night-time visits, recently.

Joh hands him a cup of beer without asking if he wants it, and Wel, still parched, actually manages to get all of the liquid in his mouth this time. Only when he’s drained one cup and been provided with another does he subside onto a stool next to the table and rub at his eyes, trying to remember where to start.

He can’t remember. The end tumbles out first, the vision in reverse, Wel’s half-formed conclusion the only part of it he can formulate: “I think I’m going to die.”

Joh doesn’t react hastily, which is one of the reasons he’s attained the position he has. He also doesn’t say something trite like we all will. He knows what Wel means. Interpreting the inexpressible is his job. “What makes you say that?”

Wel doesn’t answer. He rubs at his eyes and the black on the inside of his eyelids turns to red, which turns to memory: the knife piercing his belly, the sea of blood around him. Who else’s blood can it be?

He feels strong hands on his shoulders, shaking him slightly. “Weldjebauend, son of the sand. Tell me the vision, and allow me to be the judge of its meaning.”

Wel does. He had been trying to sleep, as the second watch approached, but he was restless. His body knows before his mind does when the god wants him; the knowledge always pools somewhere just out of reach until it reaches some sort of tipping point and he rockets upright, gasping. It feels like a fever, like having to vomit; but unlike the involuntary action of vomiting, the vision cannot start until he is in the temple. When Wel had moved out of Joh’s house and into his own small hut, he’d taken one near the temple for this exact purpose. It’s irritating to be surrounded by the crowds in peak season, but he needed to be close.

He tells Joh about the rush to the temple, his station against the statue of Amasis. He tells him about the roaring sea, that body of water he’s never seen except in his visions, his submersion in it, the knife. Joh nods; he knows all this. When Wel tells him about the knife stabbing him, he looks thoughtful. When he tells him about his physical state afterwards, Joh has the gall to actually look amused.

“Perhaps you should take a boy, Wel. I can think of a few who glance too long at you; you’d have your pick.”

Wel snorts. “Maybe,” he admits. Privately, he thinks that any boy who would want to be initiated into the pleasures and responsibilities of manhood by Weldjebauend son of nobody at all, unstable foundling seer of Siwah, would do better to have his head checked by a doctor.

Joh shakes his head. “I don’t think it’s your death.”

Even though he objectively has no more information than he did before, Wel can’t help but relax a little. Joh isn’t always right-- Wel has witnessed him interpret the gods spectacularly wrong, in fact, in ways Wel could have prevented if he’d just had the gumption to oppose Joh in public-- but on this, Wel believes him. Or wants to believe, anyway, which is the problem with prophecy: it’s easy when it’s only about other people, but it’s almost impossible to separate it from your own desires when it comes to yourself. A prophet who reads his own signs has a fool for a client.

He breathes out, pent-up air that feels like he’d drawn it in hours ago rushing out of him, and leans back in the chair. He realizes for the first time that his back aches. “So what do I do?”

“The same thing you have been doing. Go when Ammon-Re calls you, and listen to what he has to say.”

That’s it. The same thing he’s been doing his whole life, basically, but this time it feels different. It feels like something is happening, and it itches in the back of Wel’s mind that he can’t figure out what.

“And get some sleep. You look like shit,” Joh adds.

Wel nods. Maia winds her way around his feet. When he had still lived here, Wel had found her curled at the foot of his bed each morning since she was a kitten. She’s an old, sleepy cat now, and wary of him since he’d moved to his own hut and ended up keeping most of the village’s stray dogs in scraps. There’s probably dog hair on him somewhere, underneath the scents of sweat and spilled wine. He gives her a few perfunctory strokes in her head, and she ducks out from underneath him and shuffles towards Joh instead.

“Goodnight, then,” says Wel, and Joh is lumbering back towards bed almost before he’s out the door.

Wel’s route home takes him past the spring at the centre of the village. Now, just past the second watch, the water is at its warmest; it will gradually cool until it runs coldest at midday and then begins to warm once again as the sun sets. He only realizes how chilled he feels as he passes it, and reaches down to drag his frozen fingers in the warm water of the sacred spring. Steam rises from the water and buffets his face. It’s comforting. It feels like the god is his father, and is now embracing him after delivering a beating for his own good. He imagines that such things happen like that, with fathers and sons. He’s never had a father, at least not one he remembers; Joh could have claimed him as a son had he wished, but he never had. He resolutely calls him son of the sand, and only he can make it sound like an honour. Wel hears the implied message, though: not my son. He can hardly blame the elder priest for not wanting responsibility for him, now that he’s grown. He’d done enough in taking him in, convincing the priesthood that Wel was a gift from Ammon-Re and ought to be brought up to interpret the god’s desires. Whether he was correct about that remains to be seen.

That Wel is of the god is indisputable. But a gift... perhaps not. Perhaps a challenge. Hopefully not a curse.

There is a rustling in the grass, and Beddwyk bounds up-- waddles, really, as he seems to be the best out of all the Siwah dogs at begging food. He’s an old dog, and fat; Wel had stolen him from a litter of puppies out behind the High Priest’s house when he was a boy, carrying away in his arms at a sprint and terrified of being caught. He hadn’t realized until Joh had laughed at him that Ahmos could care less about dogs, and probably hadn’t even realized that there was a bitch giving birth out back.

Wel scratches him in between the ears, and stares at the stars, and breathes. His hand drags in the spring, and tingles with warmth, and Ammon gives him one last thing, opens his mouth and gives him words that ring in the air, heard only by Beddwyk, who couldn’t care less: “The son is coming.”

It’s odd: he’s been to Tyre three times, and he’s never been to the theatre.

The first two, of course, were short trips. The egersis of Melqart takes place each year at the end of the cold season, and being appointed to the Carthaginian embassy had seemed an ideal assignment for an ex-soldier with a thirst for novelty. The first two years, the Carthaginian embassy had brought their tribute to Tyre, participated in the sacrifices of quails and the ceremonial death by fire and subsequent rebirth of the god, and been on their way home within two weeks. There had been no time for any entertainment besides that of Melqart’s festival itself. This time, Alexander’s arrival had trapped them in the city for seven months; and there had been of course no theatre during the panic of the siege, during which every scrap of human creativity in the city had been solely devoted to thinking up new ways to set Macedonians on fire.

But there is theatre today. The Macedonians who managed to avoid being set on fire-- most of them, admittedly-- take up most of the seats. Their language has enough in common with Greek that Hannibal can make out some of their conversation, if he concentrates; since they are mostly recounting their glorious deeds in the siege to each other, he doesn’t bother. The conversation of the actual Greeks peppered throughout the audience is more intelligible, and more interesting. They talk about food and women and arms, but every so often in their gossip an intimation slips in-- well, but he’s serving in Darius’ force now, so who knows how that’s going to work out-- an edge of simultaneous relief at their own relatively secure position, and wonder at the world reshaping itself around them with alarming rapidity. They are here because the treaty of the Hellenes has required their cities to send them, but they are beginning to view their presence as something other than a dour requirement.

Hannibal crinkles the parchment on his knee. It’s good quality; better than could have been found in Tyre during the siege, and no worse than could have been found before. On it is an ink sketch of the same face-- always the same face, as accurately as he can recall it. He glances down at it, and away from the revival of Alcmaeon in Corinth playing out on the stage. Each time he reproduces it, he wonders if it is a more perfect reproduction of the true image, or if it gets farther and farther away. Would any man who has seen the face on the parchment even be able to recognize it, should Hannibal choose to show them?

On the stage, the actors are making jokes about matricide. “I killed my mother, to put it in a nutshell,” says the fellow playing Alcmaeon, and the actor across from him waggles his eyebrows suggestively and leers, “So was this a consensual thing, or were you both reluctant?” The soldiers of the audience snigger. Hannibal looks to where the young king is sitting. Alexander doesn’t look amused, and as Hannibal watches, his ever-present friend places a discreet hand on his thigh and squeezes reassuringly.

Alexander can’t leave without causing grave offense, but Hannibal can; and apparently unlike the Macedonian, he is not so in the thrall of Athenian culture that he’ll venerate their first-rate playwright’s second-rate work. He slips out of the theatre, and heads towards the market.

In the week since the Macedonian army had punched a hole in the wall of Tyre and taken the city, the place has undergone one of the oddest transformations Hannibal has ever seen. The atmosphere of grim duty edging on panic, the deserted streets, the poor provisions: all of that seems like a distant memory. Tyre is bustling with life again-- just not quite the life it had had before. The luckiest of the Tyrian men are already dead and burned, killed in heroic action as the Macedonians took the city. The less lucky were loaded onto triremes a few days ago, headed for the slave markets of Greece; and the hopefully-dead bodies of the unluckiest are attracting flies as they hang from their crosses on the beach. The marketplace is alive again, but the mix of Phoenecian, Aramaic and Persian that used to fill it has been replaced by an intricate linguistic war between Macedonian and several different dialects of Greek, some of which are simply merchants from surrounding Phoenicia flooding into the city and shouting out the few Greek words they know to advertise their wares.

Hannibal speaks Greek to them, because he is proficient enough that they at least don’t recognize his accent, and because it is better not to speak Phoenician, now. Not when he is very possibly the only living being in this city-- excepting the dogs-- who survived the siege from the other side. His Carthaginian compatriots had embarked their own trireme home days ago, and without him. They will interpret his failure to appear at the ship as evidence of his death, probably, and not enquire too much farther. He will need to send a letter at some point to correct the record on that point; Alanat the Rhodian is a practical enough woman that she will remarry, and though his eldest has proven rather frivolous, Hannibal is glad that he had reserved his own name to pass on to his younger son. Hannibal the Younger would no doubt find suitable men for his mother and sister as quickly as possible, should he believe his father dead, and Mismalka the Younger would be absolutely furious if she were forced to marry for the sake of her own upkeep, only to find out later that her father wasn’t dead after all. It is only with the admirable practicality of his progeny in mind that he drifts towards the stalls of the Greeks with their hide parchment, and stops also at the stall of an Egyptian selling his reed papyrus. He buys some of each; he’ll use it all eventually. He enjoys sending letters, and the more he travels, the more cause he has to send them.

Any other man would, perhaps, feel troubled strolling through the stalls of merchants come to sell to the army of the Hellenic League; would wonder if he was truly worthy of being the sole remaining survivor, basking in the afternoon sunlight and the joy of being a human in a seething mass of humanity. Hannibal is no longer troubled by the thought that there are things that ought to trouble him.

He is enjoying himself so much, in fact, that he barely minds that the crowd has become thicker; the men who had been watching the play are flocking out of the theatre and wandering the market in search of some wine or fruit. He doesn’t pay them any mind, that is, until he is inspecting a stall of pottery and someone strides purposefully up beside him to say, “You missed your boat, Carthaginian.”

Hannibal doesn’t turn to look at him, instead joining his hands loosely behind his back and leaning in as if merely interested in the detail on a vase. He had been granted safe passage from the city, and had chosen not to take it. Any of the victors would be within his rights to cut him down where he stands. “I watched them go. I cannot say the return vessel rivals the one we arrived on, but they will no doubt sacrifice in thanks for safe passage on it nevertheless.”

Hannibal had watched the dedication of the Carthaginian sacred vessel, alongside the the war engine that had made the first hole in the wall. Amid all of the death and destruction, the first time he had felt annoyance at the conquerors had been watching a builder inscribe Greek letters on the ancient Carthaginian vessel.

Alexander’s friend-- for that is who it is, Hannibal confirms with a quick glance out of the side of his eyes-- doesn’t return the barb about the sacred ship. He mirrors Hannibal’s posture, pretending the vases in the stall interest him too, and surely the two of them look for all the world like they are merely making idle chat while strolling in the marketplace. “And to what will you sacrifice now, with your god having received such a glut of prizes in the past few days?”

“That the shield of the man on my right may not fall from his arm, and that my shield may similarly protect that man on my left,” Hannibal answers promptly, “As has been my habit since I was a youth.”

“You are a hoplite?” Hannibal can hear him disguising the surprise in his voice quickly. Carthage is a naval power. For land war, she relies mostly on Libyan and Greek infantry and Numidian cavalry; some of the best in the world, but expensive and not guaranteed to be loyal to Carthage. It was the uncertainty of those allies that had caused the city to try to create an elite hoplite force, though limited in numbers.

“I was a member of the Sacred Band of my mother city, as a young man.” Hannibal takes pity on his obvious confusion, and clarifies, “We had little in common with our namesake; neither the particular means of unity of the Thebans, nor their ending. Most of my unit was cut down at the river Crimissus by the Syracusans almost ten years ago, during Theofrast’s archonship at Athens. It was not widely advertised that not all perished, since the unit was never reconstituted under the same name. That, we share with the Thebans.” He turns a little to see the other man’s face, and notes the amused twitch of his lips. Although taller and broader, he looks hardly older than Alexander. If he had fought alongside his friend when the latter had been only a youth under the command of his father at Chaeronea, perhaps he had helped annihilate the lovers of the Theban Band himself.

It would be easy for the Macedonian to make a joke at the expense of either Hannibal or the dead Thebans, but to his credit, he doesn’t. “And now?”

“I was hoping to find employment in my old profession,” Hannibal says bluntly. He had been planning on going about it more discreetly; but perhaps Melqart had approved of Hannibal’s final sacrifice in the temple after all, for now the god has sent him a powerful man asking him directly what his aims are. The king’s friend seems curious about him, but not hostile, as he had first assumed. It would be folly not to use this opportunity.

“You have never held a sarissa, I assume.”

“No.” It would take a man much crazier than Hannibal actually is to pretend expertise with a weapon more than twice as long than any he has actually held.

“Visit Parmenion son of Philotas, who for our stay here has taken up a residence between the shrine of Agenor and the Sidonian harbour. Do not go tonight, he will be drunk; but tomorrow not too long before noonday, when old men are active. Tell him that Hephaestion son of Amyntor has allowed that you be given a place among the allied Greeks. If he refuses nevertheless, however, I think you would do better to leave the city without protest than to insist.”

Hannibal nods. The arrangement is both generous, and revealing of precisely the sort of information about the Macedonian leadership that Hannibal would like to know. Hephaestion is powerful, and has the ear of the king, but he is not so secure in his military position that he would like to be perceived as giving orders to this Parmenion; therefore, although he could stick his neck out on Hannibal’s behalf if he wanted to, admitting a Phoenician envoy into the phalanx of the allied Greeks is not a cause he cares to use his influence on behalf of. Fair enough. “I will do as you say, son of Amyntor,” he says, “And either way, you have a gratitude of Hannibal son of Lectis, of the city of Carthage.”

*

Parmenion is not, as Hephaestion had half-implied, a senile old man. He is old, but his age is of the kind that the gods seem to bestow on certain old campaigners; instead of the life leeching slowly out of him it seems to have drawn in, making him wizened and compact. He has indeed taken over a house in the city, near the Sidonian harbour; his few possessions, including a hide tent, are scattered in the courtyard where he works, while the remains of the previous inhabitants’ lives still surround them. It will all be sold off eventually, just as the previous owners of this house will be, and the money will make its way to Alexander’s coffers-- assuming it encounters no sticky fingers on the way. But the details of the plunder of the city are beneath a man like Parmenion; he will simply live here until the army moves on, a comfortable place from which to conduct his business.

Hannibal has to wait in line to see him, and easily ignores the curious looks of the other men who have business with the old general. Most of them speak Macedonian to him, and Hannibal is relieved that he can pick out words from it, and will no doubt with some small effort soon be able to understand it entirely. Other visitors speak Greek and a few, their heads bowed low with the deference of the recently conquered, speak to him in Aramaic through a translator who had been lounging in the corner writing something on wax until he was needed.

Hannibal speaks to him in Greek when his turn comes. “I am Hannibal son of Lectis, hoplite of the Carthaginian Sacred Band and lately envoy to the egersis of the Tyrian Heracles. Hephaestion son of Amyntor has sent me, generously suggesting that I may find employment in the infantry of Alexander Hannimelqart, the chosen one of my god.”

Parmenion, sitting at a desk covered in clay tablets and papyrus both, draws his arms together, as if he is preparing to be told a story. He has a close-cropped grey beard and bushy grey eyebrows, which draw together as he peers up at Hannibal. “The chosen one of your god. Do you think so?”

Hannibal tilts his head curiously. “Do you not?” He had gathered already that the Macedonians do not worship their king as a god, as the Persians or Egyptians do. They even choose him by the acclaim of the men of the army. It’s an odd custom, one that he’d like to know more about.

“I think that Alexander is a worthy commander-- as good as his father, perhaps someday better. If you wish to serve him, I have no objection, Carthaginian. What arms do you have?”

“None. I came here as a religious envoy, not an infantryman; I brought my short-sword, but as I lent it to a Tyrian defender, it has been relieved from my possession.” That seems to Hannibal like a more than fair way to express it was looted by you lot. He’s done his fair share of looting himself, of course; it’s the traditional reward of the rank-and-file solder after a long and successful action. That doesn’t mean he enjoyed watching his stuff being carried off.

Parmenion chuckles, evidently having expected something of the sort. “Kleandros son of Polemocrates will see you outfitted, and placed with a battalion of his Greeks. Your speech is good, though I think you had best remain on good terms with your fellow-soldiers, or sleep with one eye open.”

“Discourtesy is unspeakably ugly to me,” says Hannibal. “I would not exhibit it, but nor would I tolerate it.”

The old general scoffs, not unkindly, and pulls a piece of papyrus towards him. “You’re a soldier again,” and there is an edge in his voice suggesting the shared experience of those used to being older and more experienced than those around them. “I suggest you learn to tolerate it. Take this to Kleandros, who is still camped with his Greeks on the mainland. It is an order that you be given a place in his battalion, and provided with the necessary panoply.”

Hannibal takes the slip. At the top, it says “A very odd type. Thought you might enjoy a Carthaginian for your menagerie. Best of luck.”

“I--” can read Greek, is about to come out of Hannibal’s mouth, but perhaps it would be better for that to not be known. “--thank you,” he finishes instead.

Parmenion nods brusquely, and turns his attention to his next supplicant.

Hannibal has no belongings of note to gather; he has been sleeping at the temple with the other spared Tyrians, but it has been emptied of all goods of value. He is unsentimental about the men inside of it; but there is, stashed away in a loose tile in a back room, the remainder of the money that he had brought with him. He had intended to use it to buy some pretty things to bring back to Alanat; but once the siege had started there had quickly been nothing much in the city worth buying, and now it sits unused. He glances at the papyrus again. Kleandros had been ordered to see to his panoply, but Hannibal suspects that supplying him with a tent will not be a high priority for his battalion leader, and all of the eight-man tents are likely filled. They won’t appreciate an interloper asking to sleep in them. The coins are decent electrum shekels from the mint in Lilybaeum; there should be no issue finding a merchant who will take them.

All of the men of the temple of Melqart are in the sanctuary, praying, when he enters; he doesn’t greet them as he makes his way past, and he doesn’t say goodbye on his way out. The marketplace is still bustling, though Hephaestion is nowhere to be seen. Hannibal has no problem in acquiring a small tent-skin, as well as an extra plain linen chiton, a Greek-style wool cloak, and a broad-brimmed Thessalian sunhat-- a somewhat distasteful form of headgear compared to the pointed Phoenecian silk cap he had left behind in the temple, but more useful for keeping the sun off of one’s face during long marches. The only problem with the items is that they are rather too new and nice; a foreigner with a too-nice tent is liable to find it snatched from the baggage train and replaced by someone else’s ratty old garbage. Still, nothing to be done about that but hope that he is able to identify the offender and have a word with him later.

A row-boat used to be required to get from the island of Tyre to the mainland. Hannibal walks out of the city through the rubble of the gates, and marvels for the first time from ground level at the mole the Macedonians had built linking the island to the land. Already the water lapping against it has begun to deposit sand and silt on the sides of the artificial pathway; unless it is somehow dismantled, which seems unlikely at this juncture given that most of the Tyrian citizens who might attempt such a thing are now either dead or enslaved, the water will continue its work until no casual observer will know that Tyre was once an island.

He makes his way out onto the mole, mud and rocks infiltrating his sandals. Waves lap at the sides of the pathway. He’s not alone out here; it’s busy with soldiers camped on the mainland making their way in and out, and merchants from all over arriving to take advantage of the glut of business. He steps to the side to allow people to pass around him, and turns around to look at the city. It’s the view of the men who had spent months toiling to overthrow her; thick, imposing walls, which up until a few days ago were bristling with flaming arrows.

Hannibal has never felt particularly close to his fellow man. The closest he has ever felt to humanity has been in phalanx formation: a part of a whole that moves, lives and dies as one. And yet the reason those moments call to him are intensely individual: the smell of blood, the crunch of your spear punching through flesh, the knowledge that death could come for you at any moment. So he tries to imagine the sense of purpose and togetherness of the men who built this pathway through the sea, the shared bloodlust and brotherly love, and in the absence of the warm press of bodies around him, he can’t quite do it. All he can feel is his own bloodlust, staring up at the ruined wall like he could storm the city on his own.

He turns around, and heads towards the mainland. Soon he will be back in the phalanx, feeling the reverberations of his neighbour’s spear hitting home in his own body, knowing that his neighbours can sense his kill as well.

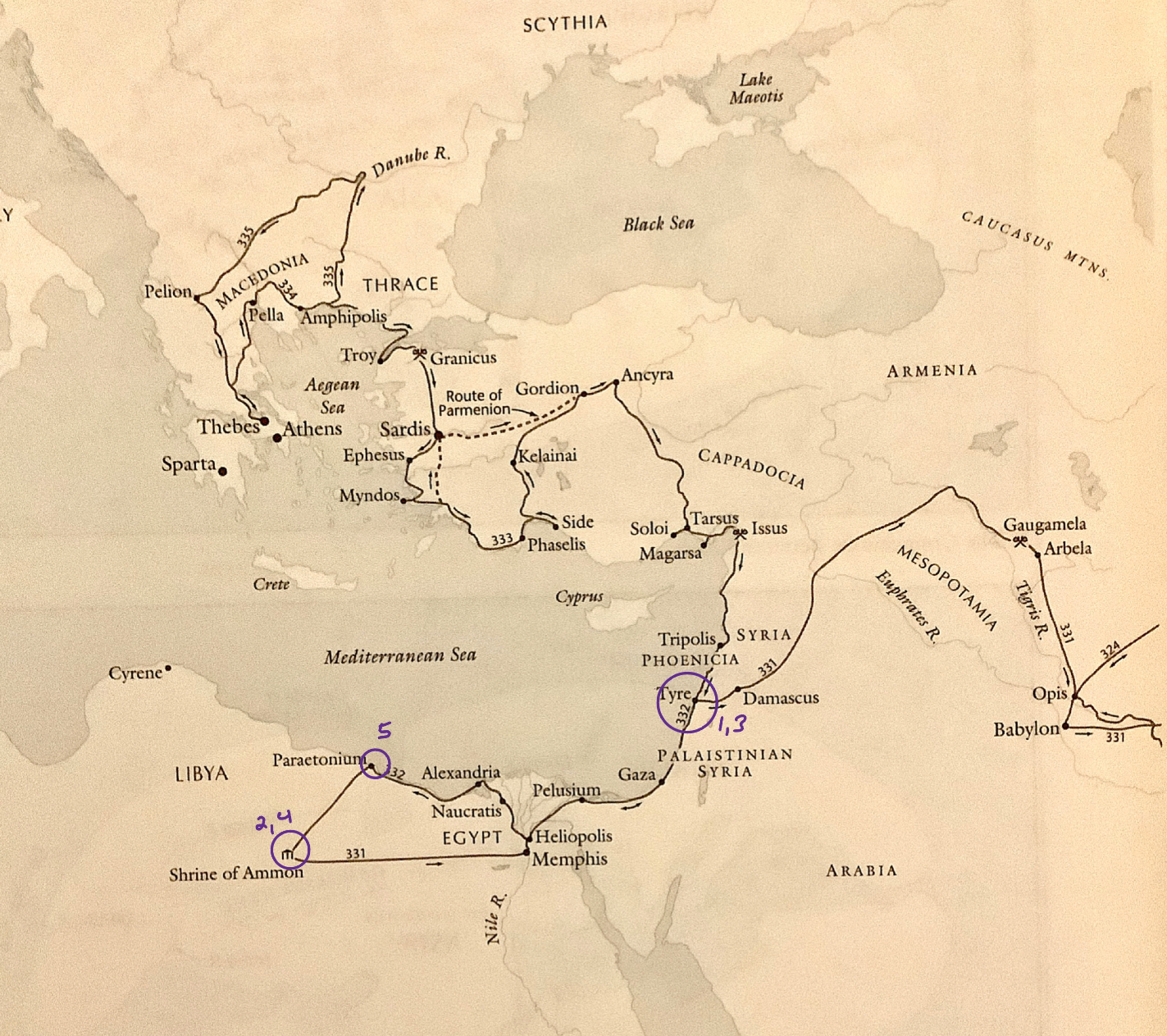

It’s sweltering hot, but the High Priest has decided to hold this meeting outside. Such practicalities are unfit for the eyes of the gods; apparently this is how it has always been done, in advance of a major arrival. Wel squints into the sun at Ahmos the High Priest, grizzled, stooped and thin, who is handing out duties to the temple workers who are not themselves soothsayers of the god. Unlike most visitors to the shrine, who find their way to the temple themselves, receive what wisdom Ammon has to dispense, and leave, this one is to be greeted at the entrance to the oasis village. A house has been prepared for him and several other huts emptied out for whatever friends he wishes to give them to for the duration of their stay, and arrangements for food and water to be brought immediately to the soldiers he would be bringing with him.

Wel is sitting beside Joh, who has been muttering steadily this whole time about how the contents of this meeting could easily have been decided in advance and sent to the homes of those involved on wax, instead of sitting in the sweltering heat listening to Ahmos get deep into the weeds of salt rations. At the mention of soldiers, though, he raises his head from where he had been staring at his fingers and says, slightly louder, “What soldiers?”

Ahmos ignores him. The High Priest had received a messenger from Memphis that morning, a Libyan with a lovely tall dromedary who specializes in traveling quickly through the desert and not losing his way in the sand-storms. Age has not tempered Ahmos’ love of importance; clearly, whatever information the Libyan had given him has made Ahmos feel very important indeed, and he is loathe to distribute it too quickly. Wel lets his mind wander back to the dromedary, whom he had been permitted to feed and stroke as Ahmos and the messenger had talked. He’d rather go back and spend some more time with it, or with the dogs.

Eventually most of the temple staff have been assigned duties and dismissed, and it is only the actual priests of Ammon left. “Thothmose son of Ramessu, Menes son of Seth, Weldjebauend son of the sand. Which among you speaks the best Greek?”

Joh looks up from where he’s been scratching designs into the dirt with a stick; it’s the first hint of the visitor’s identity they’ve had. Joh had insisted that Wel learn Greek as a child, since the shrine does get wealthy Greeks sometimes, and is always looking for more temple acolytes or priests on hand to prophesy or translate for them. It had been, transparently, a way of making Wel useful even if Joh’s prediction that the desert foundling would grow up to be favoured by the sight of the gods turned out to be wrong. Wel had sensed as a boy, though not understood the reason until much later, the edge of desperation to the subjects that Joh had chosen to have him educated in, and consequently had studied them carefully. Since Wel’s gift for prophecy had turned out even stronger than Joh had hoped, however, his Greek is merely convenient, instead of a necessity to maintain his usefulness to the temple.

It’s also not particularly fluent, since his only opportunities to practice have been the occasional Greek visitor. Menes, who had spent time traveling before joining the Siwah priests, speaks much better. Wel gestures to him, and Thothmose-- who can barely speak Greek at all, but is confident enough with his limited skills that visitors tend to find his rustic accent charming even when incomprehensible-- concurs.

“Good. The son of Seth will interpret the will of Ammon for the guest. Myself, Joh son of Ḫanabeš, Khafra son of Paphnutius, and Thothmose son of Ramessu will carry the vessel.”

There is an odd silence over the entire assembly. Wel is mostly irritated that he’s been forced to attend a meeting about a special visitation only to be told there is nothing for him to do; but he can feel, too, the edge of surprise about what Ahmos has just announced.

The vessel of the god is in the shape of a long, flat boat, from which many precious objects, including the heavy round stone that symbolizes Ammon-Re, are hung; the vessel is held with long poles on the shoulders of the priests. There are basically an inexhaustible number of poles stored in the back room of the temple, because the vessel is damn heavy and it’s best to have as many people as possible help hold it. Ammon-Re’s will is translated through the movement of the vessel into the bodies of the priests, who dip and sway in response to the shifting of their burden. The priest charged with interpreting the will of the god for the supplicant-- in this case, Menes-- reads the prophecy from the movement of the vessel and the men underneath it.

On a busy day a dozen men can work the vessel from sunup to sundown, with one or two taking a break at a time. On a slow day, six or eight will do. Four men could probably carry out a single prophecy, with difficulty and aching legs for days afterwards. But there are priests to spare in Siwah, and there has never been any reason for them to.

“Who the fuck are we prophesying for here, anyway?” says Joh.

Only Joh-- acknowledged as second-in-command to Ahmos, although there is no official ranking of the full priests-- could get away with addressing him like that under normal circumstances, but Wel watches the high priest draw himself up to his full height and take a deep breath and thinks that actually, this time anyone could have said it: Ahmos has been just bursting at the seams with excitement over getting to say whatever he’s about to say, and Joh had set him up perfectly.

“The Pharaoh!”

There is a silence. The air seems to be buzzing slightly. Wel feels the approach of the tide of blood from his vision as if it were lapping at his toes. He has the absurd urge to take off his sandals and wade in.

Thothmose, who is brave and cheerful but not all that bright, blurts out “Er, not to state the obvious, but if Darius of the Persians is coming to seek prophecy, then we ought to address him... in...”

He trails off at the absolutely withering look directed at him by Ahmos. It would be warranted even if he weren’t completely failing to put together the information he’s been given; nobody calls Darius the Third Pharaoh unless they’re being paid to do it, just as they hadn’t called Artaxerxes Pharaoh before him. The Pharaoh is appointed by the gods, to serve as messenger between them and the mortals of Egypt. Why would the gods appoint a conqueror who prohibits their worship? Why would the gods appoint a Pharaoh from among the Persians, who killed the sacred calf of Hapi-Ankh and put to death the Egyptians showing him his proper rites? Few in Siwah, isolated enough to allow them to form their own opinions, could believe it. The Persians must therefore be usurpers, pretenders, hated by the gods. If it were Darius making a visit to Siwah, they would prophesy for him in Aramaic and call him Pharaoh to his face; but certainly not at this meeting.

Thothmose’s stupidity works in Ahmos’ favour, who was waiting for an opportunity to continue with the appropriate rapt attention from his audience. “I have received credible information that a month ago Alexander of the Greeks, who sent Darius of Persia running like a little boy from battle at Issos, entered Memphis. And on that day a flash of lighting came from the heavens, and a calf was born such as has not been for these last ten years of false rule: with the white square on his forehead, and the eagle on his back, and the beetle on his tongue. And Alexander was the first to sacrifice to the newborn calf of Hapi-Ankh, and gave splendid sacrifices also to the other gods, and was crowned Pharaoh Setpenre Meryamun by the people of Memphis on behalf of the gods, who have received at long last their proper worship. Setpenre Meryamun then founded a city near the sea which received favourable omens from those that read the birds, that it will be prosperous in every way and feed many other nations. He now desires to consult Ammon-Re, as is good now that he knows that he has been chosen as liberator and leader of Egypt.”

In the thoughtful silence that follows, Beddwyk ambles into the clearing where the meeting is being held. When nobody immediately holds out anything for him to eat, he turns by default towards Wel, who silently reaches out to scratch his ears. A wave of recognition washes over him; he’s been here before, sitting with Beddwyk and knowing, on some level, exactly what he has just been told. The son is coming, he had prophesied, one of those off little one-offs where his mouth is commandeered for the use of the god without an accompanying vision. He tends not to pay them much mind; prophecy is one thing, and has always come to him with no effort, but interpreting prophecy is quite another, and a single phrase rarely gives enough information to be interpreted with any accuracy. But now the meaning of this one is clear enough. The Pharaoh is, by definition, the son of Ammon-Re; though many had privately not considered the Persian Great King to be Pharaoh, the omens associated with this new one-- and Wel’s own prophecy-- show him to be truly appointed.

Wel comes back from his contemplation to conversational chaos; now that the identity of the guest has been revealed, everyone has questions. Where is this Greek from? Who was his mortal father? Is Darius dead? What kind of bird provided the omens at the site of the new city, and what did they do exactly? Has he a wife? A son? Does he also give orders in Aramaic, like the Persians? Or perhaps does he even speak Egyptian? What will he ask of the god?

Ahmos, who clearly doesn’t have good answers to any of these questions, vaingloriously tries to answer them anyway. Meanwhile, the one real question that Wel had had has been answered: why only four men to carry the vessel? Clearly, because Setpenre Meryamun will desire privacy for his questions, and the fewer men present the happier he will be.

Wel looks around. It seems like the main point of the meeting has been disseminated, and Wel’s contribution to the Pharaoh’s visit is to be sitting at home twiddling his thumbs. If that’s the case, he might as well get a head start on it. He’s pretty sure nobody but Joh notices when he slips away.

“So,” Briareos son of Zenos says. He is waving in the air the long stick he had used to scratch four lines in the dirt, which themselves had written on top of countless other sets of lines. “As AB is to ΓΔ, so E is to Z. AB is the greatest, and Z the least. And let’s add H on AB and Θ on ΓΔ, so that AH is equal to E and ΓΘ is equal to Z. So as AB is to ΓΔ, AH is to ΓΘ, and as...”

Hannibal leans forward as Briareos continues in a kind of maniac mutter, tracing lines on lines. He does in fact seem to be saying only true things about his lines, though he’s the only one quite so excited about it. “Thus, if four magnitudes are proportional then the largest and the smallest of them is greater than the remaining two,” he winds up triumphantly, “Which was the point all along!”

“Sure it was,” says Jason son of Prokopos, who is lying back against a tree in a fashion that suggests he’d not watered his wine very well at dinner. “You’re always right to the point. Very pointy. Positively priapic.”

Bacaxa taps her fingertips on her chin, and says what Hannibal’s thinking: “Okay. Is that all?”

“What, like there should be more?”

“Well. Let’s just say you talked up this teacher of yours enough that I started to wonder why I hadn’t heard of Eudoxos’ innovations to the construction of siege machinery, and now I know.” She returns to what she had been doing, which was carving a wooden doll for a child out of a broken piece of wooden winch-handle from an oxybeles. She seems to be making decent money selling them-- any campaign picks up wives and children the longer it goes on, and this one has technically been on the road for five years now-- and Hannibal hasn’t seen her without her knife and a piece of scrap wood lately.

Though she probably has other reasons for carrying the knife, which Hannibal tries not to think on. Despite Jason and Briareos’ warnings not to, he’d once offered to escort her safely back to her tent with the rest of the Phoenician engineers. It had been the very first night of his own presence by Jason and Briareos’ evening fire; she had lingered, and he’d thought perhaps she’d accept from a Carthaginian the courtesy she wouldn’t from an Athenian. He’d found himself instead with the sharp point of a blade pressed to his belly. “Say that again and I’ll eat your insides for breakfast,” she’d hissed, which entirely cleared up all his previous objections to her presence.

Now she sets aside the knife and picks up a minuscule chisel to work on the face. Briareos slumps back down in between her and Hannibal, scuffing the remaining lines into the dirt with the sole of his sandal. “All right. But don’t blame me when you shrivel and wilt for lack of intellectual stimulation. You won’t be able to siege anyone for at least a few weeks. Are you sure you’ll survive?”

“There’s plenty to do. All of my babies are going to have their sinew replaced before the next one. Wait, what do you mean, won’t be able to? We could have the machines ready for tomorrow, if we needed to.”

“Paraetonium wasn’t just a sight-seeing expedition,” cuts in Jason. “Word is, there’s that oracle in the desert near here, that Heracles supposedly visited. And--”

“--what Heracles did, our boy does too,” says Briarios.

“But more ostentatiously.”

“Right. But only the ugliest and hairiest-- sorry, strongest and fastest-- Macedonians get to go starve in the desert with him. The rest of us will be camped out here until they come back with him having sprouted horns behind his ears or whatever he’s hoping to do out there.”

Bacaxa drops her tools into her lap. “Wait, Alexander’s going to Siwah?” she says. “Well shit, I want to go.”

Jason and Briarios glance at each other skeptically in a way that they either don’t realize is incredibly obvious every time they do it, or don’t care. “Er,” says Jason finally, “I don’t think... I mean, I doubt even the common Macedonian men are going to get anywhere near the temple. So I’m not sure a...”

He trails off before saying Phoenician woman, but when Bacaxa just glares at him, he finally finishes “...engineer would really have much to do.”

Bacaxa pushes herself to her feet, and levels a scathing glance at Jason as she says, “Everyone needs... engineers. It must be geometers you’re thinking of, who don’t have anything to do.” She stomps off into the night, her shadow flitting between fires, gatherings of men who watch her pass uneasily.

It not that late, especially on a night when there is no early march in the morning. But Jason and Briarios are clearly just warming up for the kind of bickering that old married couples can only dream of, and they wave him good-bye absently when Hannibal announces his intention to turn in. He returns to his tent, which had indeed been stolen and replaced by a lower-quality item in the baggage train within three days of his presence. He knows the culprit by sight, but it can wait. The tent does well enough. Just before he is about to enter, he changes his mind, and skirts around a couple fires to follow Bacaxa.

She doesn’t seem all that surprised when he catches up to her. “Come to remind me that I’m inevitably going to be raped, murdered, and my body picked on by desert birds?” she snipes, in her stilted Greek. Her speech has the aggressive oddness of one who knows they don’t speak a language well, doesn’t care all that much, and speaks confidently anyway. It’s both charming and somewhat repellent.

Though rape has never much appealed to him, Hannibal has admittedly already considered murdering her and throwing her body to the birds. Bacaxa had been on the team of Phoenicians who had come over to Alexander along with the navy at Tyre. Habsan, their leader, had offered the group as a whole: a dozen of the famed Phoenecian military and naval engineers, take it or leave it. Alexander, never one to turn down allies just because they didn’t look like he thought they would, accepted. The fact that Bacaxa was part of the package didn’t seem to bother the high-ranking Macedonians, but the common men and the Greek allies were a different story. And Hannibal, who had grown thinner inside the walls of Tyre while Bacaxa had fine-tuned the machines knocking them down, would easily be able to justify killing her for her betrayal.

But whatever pleasure would be gained from the crunch of her bones and the tear of her flesh would be outweighed by her absence. He likes the world better with her in it. And in any case, if Bacaxa has betrayed her people, so has he: he’s here, well-fed and warmed by fire after sitting in friendship with Alexander’s diffident Greek allies.

The Greeks, so far as he can see, aren’t called upon to do much. As a member of the Athenian unit of the phalanx-- Kleandros’ idea of a joke-- Hannibal’s main contribution to the siege on Gaza, taken immediately after Tyre, had been to have a fire ready for Bacaxa for whenever she was finished repairing the day’s wear and tear on the war engines. Jason and Briarios, despite their tendency to finish each others’ sentences and descend into bickering at the slightest provocation, turned out to be the most welcoming of his Athenian fellows. Almost too-stereotypically, they both frequented the same philosophy teacher back home, who had encouraged them to view their mandatory military service to the near-barbarian at the head of the Hellenic League as an opportunity to view the peoples of the world like specimens, and report back to the civilized bastion of Athens with their findings. Hannibal and Bacaxa are their two favourite oddities to study.

“What is there at Siwah that is important to you?” he asks her in Phoenician. It’s a small intimacy, to speak in their own language together; he’s mostly curious if she’ll allow it. She glances at him warily, weighing him as they exit the portion of the camp housing the Greek allies and turn to skirt the edges of the Macedonians. Bacaxa’s colleagues are on the far side, well out of the way of any drunken soldiers happening to wander off. Most of them are old men, and guard their sleep preciously.

“The oracle is said to be truthful,” she replies-- in Phoenician, and Hannibal feels a small glow of triumph. “Isn’t that enough?”

“Not if you never get near enough to consult it,” Hannibal answers, because Jason is right: even setting aside the issue of her womanhood, there will surely not be enough time or will for the common soldiers to ask questions of the god who lives there.

Bacaxa thumbs the handle on her knife absent-mindedly. “Oracles are a place for meetings,” she says finally, softly.

That’s true enough: such a meeting had supposedly produced Alexander. “Whom do you wish to meet?”

“Nobody. I won’t see them again on this earth. But my parents met there. I guess I want to see what they saw.”

“Are they dead?” Given how far they’ve all already travelled, it seems unlikely to Hannibal that there’s any place on the earth her parents could be that Bacaxa would not be able to visit. But he wants to hear her say it; he wants her to have said it to him.

She is very good at this: she sounds merely like she’s telling an interesting story as she says, “My mother died in battle when I was little. It was supposed to be just a patrol, nothing major-- you know how those years were on the island outposts.” Hannibal does; he had spent the years of uneasy peace between Carthage and Syracuse on similar patrols, which turned bloody just infrequently enough for it to be unexpected every time. Some of the Libyan tribes train women in war; he’d never seen them, but he’d known they were present in Carthage’s mercenary force.

“And your father?”

“Fever. Just a few years ago. My mother had intended to bring me home to her village and train me in her profession, but she died before I was old enough. My father was Phoenician; he trained me in his instead. I think it was his way of honouring her.”

“And do you expect her shade would be pleased to see what you’ve become?”

Bacaxa stops, turns to look at him. They’re in a gap in between the nearest fires of the Macedonian camp and the outskirts of the engineers, a no-man’s-land of darkness. “I think she’d say I’m too skinny and should carry a longer knife. Other than that, yes. Hannibal, what do you want?”

Hannibal is surprised to realize he’s not actually sure. His desires are usually clear to him: bloodshed, good bread, good meat, pleasant company. But he had followed her knowing that there was something for him here, and he’s not sure what it is.

Bacaxa, it seems, does. She inclines her head at him, an odd half-nod that she throws casually at soldiers like she’s studied the offhanded casualness of manhood and is mimicking it back to them. “You want to go. Don’t you?”

“What reason would I have?”

Bacaxa’s eyes narrow. She studies him like Briarios and Jason only wish they could: like she can see right through him. “You have every reason,” she says. “You act like you know exactly who you are and what you want, but really, you’re as lonely as a shipwreck survivor. You’re alone, even when you’re charming Athenians left and right until they almost forget you’re not one of them. You’re looking for something. I don’t know what it is. But I think you should go.”

For a moment, Hannibal sees red. It would be so easy to reach out and snap her neck, just like he had done to that idiot outside the temple of Melqart in Tyre. It would be so easy to turn her from knowing something about him, into a slab of meat.

He doesn’t. Life is full of many such opportunities; they must be chosen with care. “How were you planning on being assigned to the expedition?” he asks instead.

“Don’t know. I was going to ask Habsan. I think he’d want to help, but-- even if he could get an engineer assigned...” she trails off unhappily.

In a moment, Hannibal makes a decision. It may not be a good decision, but he has rarely regretted his impulses in the past; and Bacaxa is right. If the evidence of Hannibal’s unavenged blood-feud is truly that obvious, written on his body as if he were already drenched in the blood he is owed, then perhaps a sacred place is what he needs. “Have Habsan put me forward, under the names of one of your colleagues,” he says, “and claim you are my wife. Of the Macedonians only Alexander, Hephaestion and Parmenion could know me by sight; we’ll have to keep out of the way during the march, you especially.”

He can see her jaw clench. He already knew that it was rarely a good idea to point out to Bacaxa the consequences of her womanhood; she knows them all already. And yet it’s a better shot than she’d have on her own, and he’d left an opening for her: a deliberate vulnerability that might soften the blow of the one being forced on her.

“So I was right,” she says. “You want to go.”

Truth is the price of her agreement to his terms. It’s one he’s demanded often enough; he has no issue with offering it to her. “Yes.”

That night it rains, and hard. Wel can hear the droplets bouncing off the roof of the house, practically taste the salt on his tongue. He’s felt feverish all night, some sort of anticipation that’s different from the feeling of an impending vision, and the rain sounds welcoming. He leaves his clothes in a heap on the floor and steps out into the downpour. It hits him like a solid weight, and it takes effort to turn his face up to the sky and squint into the clouds. Rain isn’t so unusual at Siwah, but it’s usually a polite sprinkle; sent by the god to replenish the waters of the village and keep the crops growing, nothing more.

This is different. The enormous raincloud stretches out to the horizon. Wel has the sudden urge to take exercise; he’s been sitting all day, and something about the rain’s wildness requires matching in the body. He runs through the streets of the village in loops until he tires at the same time as reaching the edges of the oasis. He stops, staring out into the desert. It is raining there, too; soaking the sand and packing it down tightly. It will dry up quickly, Wel knows. But for now the vast stretch of desert between Siwah and Paraetonium, the closest coastal city, seems almost hospitable. Setpenre Meryamun and his soldiers must be making their way across the desert, and Ammon-Re has sent rain to ease their journey. Then Wel bursts out laughing, imagining the Pharaoh arriving at the oasis right this minute and being greeted by a grouchy, tired priest naked and soaked in sweat and rainwater. He heads home and spends the rest of the night shivering, cuddled up to Beddwyk to try to regain his warmth.

The next morning the water has dried up from the desert, and from the edges of the oasis, there is a sand storm visible on the horizon.

Joh finds Wel standing there, watching it. It’s far enough away not to threaten Siwah, but they’re both thinking the same thing. Joh is the one who actually says it out loud: “Well, so much for our new Pharaoh.”

Wel swallows. Joh is right. A Libyan, Egyptian or Nubian accustomed to the desert, with a good dromedary and wise in the ways of snakes and birds, might be able to find his way back to the coast after a sandstorm. But the storm has no doubt buried the markers that show the way from Paraetonium to Siwah, and the Pharaoh is a Greek. Anyway, the sand would be entirely capable of burying an entire army if Ammon-Re willed it.

Still, Wel feels nothing; no oncoming vision or prophecy, no sense of whether Setpenre Meryamun is dead or alive. The god apparently wants him to wait. That’s its own kind of prophecy, he thinks, and shrugs. “Whether he is dead or alive is the god’s decision.”

A few days pass in a state of stasis. Few other travellers arrive; apparently the Egyptian coast-dwellers, who had received the news of new new Pharaoh significantly more promptly than the Siwans, have temporarily lost their appetite for prophecy amidst the excitement. The news of Setpenre Meryamun’s exploits prior to his arrival in Egypt also explains why the number of Persian visitors has dropped off significantly: they’re all being called up to military service as Darius prepares for a final confrontation.

A couple Libyans and Nubians show up, ask counsel in small matters, and depart quickly. They have no interest in sticking around to see the new Pharaoh. “Sounds like he’s got quite enough to be getting on with. I’d rather he never know where my village is, thank you very much,” says a Nubian named Hedjkh, who has come to ask about his brother’s health, when Wel mentions it to him after finishing his prophecy.

Wel figures that’s fair, and watches the man point his dromedary south across the desert with a strange sense of envy. Persian control over the Nubians was shaky to begin with, and certainly not guaranteed to Setpenre Meryamun as a matter of course. Hedjkh’s village can now do whatever they like with the tax collector appointed by the third Darius, and from the sounds of it “whatever they like” is going to be very unpleasant indeed for the Persian. They have no need for the Pharaoh, liberator or no.

Hedjkh’s dromedary’s hooves kick up dust in the desert. Wel has ridden a dromedary a few times; to the marketplace in Memphis the one time he went, and around the village when a visitor has brought an especially fine one and is in the mood to show it off. He’s ridden a horse once, when a Greek had brought one and allowed it. But he’s never really gone anywhere.

Most of the time, he doesn’t feel it as a loss. Being at the oasis, far from the city, suits him. Living in a hut of his own suits him, and spending what time the god allows him vision-free with the village dogs suits him. He’s not sure exactly what it is that Hedjkh has that he wants, but he watches the man grow smaller and smaller as he makes his way across the desert and almost wishes it was him disappearing into the horizon.